Ben SchofieldPolitics correspondent, BBC East

Ben Schofield/BBC

Ben Schofield/BBCThe start of the school year saw the Education Secretary Bridget Phillipson warn parents about the need for children to attend classes.

Data suggests half of pupils who missed lessons in the first week of term last year went on to become persistently absent.

But school leaders say they are seeing more children who find attending school too traumatic.

What is it like having a child with what psychologists call emotionally based school avoidance and what should be done to help?

Family handout

Family handoutThe final time Julie took her daughter to school in July 2023, a member of staff congratulated her.

Rosie, who was then eight, was “wearing a dirty pyjama top, a pair of jogging bottoms, a pair of trainers with no socks, she had her headphones on, she was holding a teddy”, Julie recalls.

“I walked into school and the [special needs co-ordinator] then said to me ‘well done, you got her here’.”

But for Julie, 48, it was not a “win”.

“She couldn’t even speak, she hadn’t eaten, she had maybe three or four hours sleep.

“But I’d done a good job as a parent for making her go to school?”

Family handout

Family handoutAt the time Rosie, who has autism, was in Year Three at a primary school in Northamptonshire.

Julie says her daughter had struggled with the school environment since her time in nursery and is now educated out of school.

Rosie, she recalls, was “in fight and flight the whole time” she was in the classroom, which “just overwhelmed her”.

Eventually Rosie was “begging not to leave” the house for school and was self-harming, sometimes on the school run.

“She would have night terrors – she would be up screaming, if she went to sleep at all.

“It just felt as if I was walking her into the lion’s den every single day,” she says.

Meanwhile, Julie and her husband James received letters and home visits from school staff about Rosie’s attendance.

“It was very lonely.

“All of a sudden there’s these letters and people are talking about fines and I was lost.”

On that final say Julie says she “dragged” Rosie to school because “that was the expectation”.

Now she wishes she had taken Rosie out of school earlier.

“But I also feel that if I hadn’t have got to the point… where she broke, I would never have known if it had worked,” she says.

Ben Schofield/BBC

Ben Schofield/BBCBased on Rosie’s reaction to school, an educational psychologist who assessed her noted she had “emotionally based school avoidance” or EBSA, a condition school leaders say they are encountering more.

Anna Hewes, the head teacher of Prince William School, a 1,400-pupil secondary in Oundle, Northamptonshire, says schools are seeing a “big increase” in EBSA among pupils in Year Seven, Eight and Nine.

The transition to secondary school is, she adds, a “key time” and at the start of the school year EBSA is “at the forefront of our minds because of the new year sevens coming through”.

The “noises, the bustling nature of a school – the busyness, all the classes walking around” make it a “real challenge” for those with sensory needs, she says.

But more generally “it’s very tough to be a teenager these days”.

Smartphones and social media, she adds, mean “young people can’t escape anymore”.

“It definitely is a post-Covid spike and these young people are genuinely really struggling to step over the threshold of the school and sometimes leave their bedrooms.”

DJ McLaren/BBC

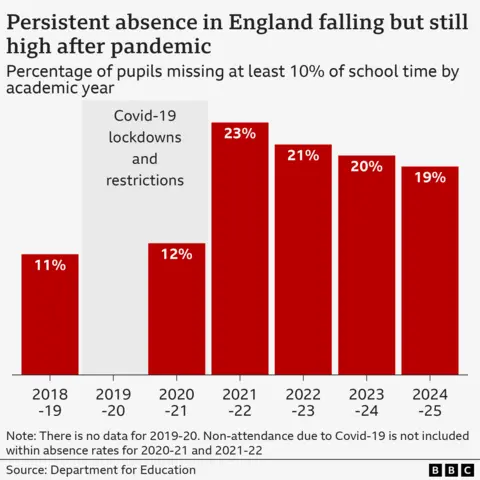

DJ McLaren/BBCAcross England, rates of “persistent absence” – when pupils miss 10% or more of lessons – have remained high since the pandemic.

Last academic year almost 19% of pupils were persistently absent, compared with 11% in 2018/19.

Mrs Hewes says EBSA is a “significant part” of the issue.

A lack of reliable data, however, means it is difficult to know how big a part.

Mrs Hewes says Prince William Academy prioritises “inclusion” and has recruited an assistant head teacher for “belonging”.

It has also opened a specialist “school-within-a-school” for pupils with EBSA, funded by North Northamptonshire Council. Four students have been enrolled so far and by 2028 it expects to see 48.

Jenny Nimmo, the head of inclusion at East Midlands Academy Trust, which runs Prince William Academy, says the unit will have more “homely” classrooms and on-site mental health provision.

She hopes it will be “future proof” because EBSA “isn’t going away”.

There are, she adds, “more and more young people” with “emotionally based school avoidance and indeed anxiety”.

Ben Schofield/BBC

Ben Schofield/BBCThe Compass Centre in Luton also help pupils with EBSA access education.

Dr Joanne Summers, Luton Borough Council’s principal educational psychologist, says the condition can appear suddenly but “when you look back, there has been anxiety around being in school” and one incident might be a “catalyst”.

Intervening early, she adds, is important, as falling behind on school work and losing contact with friends can make anxiety worse.

Dr Summers says Luton has been trying to move away from seeing school absences as “defiance and truancy”.

“We are being curious about what’s going on for that young person, why is it that they are behaving in this way,” she adds.

Ben Schofield/BBC

Ben Schofield/BBCGeoff Barton, a former head teacher in Suffolk and previous general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders, says there should be more “emphasis on the humanity of our schools” rather than “draconian discipline” over absences.

He is researching special educational needs (Send) provision for the left-leaning think tank the Institute for Public Policy Research.

He says the people he is speaking to are “universally saying” that anxiety among pupils has increased.

But the “age of anxiety” is only one reason for persistent absence.

Another is poverty, while he says there is also a “long shadow in education of Covid” when “schools started to feel a bit more of an optional decision”.

Cornelia Andrecut, the executive director of children’s services for North Northamptonshire Council, said the authority has offered training courses for schools to learn strategies to support children with EBSA.

The government says it will spend £740m creating “more specialist places in mainstream schools” and placing Send leads in 1,000 new family hubs.

A Department for Education spokesperson says: “Schools should take a ‘support first’ approach for children who are facing barriers to regular school attendance, and we are expanding access to mental health support teams in all schools, ensuring that every pupil has access to early support services in their community.”

Family handout

Family handoutFor Julie, taking Rosie out of school was “not a lifestyle choice” but was prompted by “trauma and distress” that her daughter is still recovering from.

Does she regret pushing Rosie to attend school?

“Yeah – definitely.

“I always wonder if there was a bit of trust broken between us as mum and daughter when I still took her into that place when it was that bad.”

Comment ×